Excessive Immigration Hurts Birthrates

When migration overwhelms the housing supply, fertility plummets

Housing costs are a big barrier to having kids in the US and other countries. Where immigration exceeds the ability to add housing, young people are priced out.

The building industry can’t keep up

Immigration can bring a lot of benefits, but there are also costs, and housing shortages are often one of them. Housing limitations are a big reason why excessively high immigration rates are not feasible. The housing stock of a country increases gradually, but immigration can overwhelm housing suddenly. Elon Musk explained the problem back in January:

Housing shortages related to very high immigration are already occurring in the United States. Even though US fertility has been below replacement for 50 years, there aren't enough houses for families that want them.

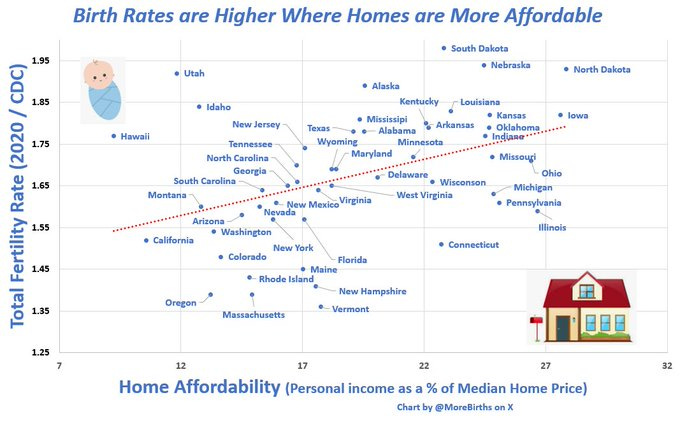

House Affordability is a Causal Factor for Birthrates

The relationship between housing affordability and fertility rates has been well established in numerous studies. This can easily be seen among US states. Where homes are more affordable in relation to incomes, fertility is higher.

When homes are too expensive, young people are often stuck living with their parents. As demographer Lyman Stone showed in a study across many countries for the Institute of Family Studies, when young couples live with their parents, they tend to have far fewer children.

For fertility, it is crucial for young people to start living independently early in adulthood, but this is very hard to do when there is a housing shortage.

The Case of Canada

Canada offers a cautionary tale of what happens when immigration overwhelms the housing supply. No country in the world has higher net-migration per capita than Canada.

Meanwhile, fertility in Canada has plummeted to just 1.25 births per woman in 2023, meaning Canada has by far the lowest fertility among Anglosphere countries and one of the lowest fertility rates in the world. Why is fertility in Canada suddenly so low?

The lack of sufficient housing is surely a big reason. Home prices have tripled just since 2000, and housing has become the top political issue in Canada, pushing a generation of young people to the right.

Making matters worse, much of the housing being built in Canada is small apartments in high-rise towers. These are generally anti-natal. Canada really needs more of the single-family homes most sought after by people wanting children. The supply of those is much harder to increase.

While falling fertility in Canada has multiple causes, the immigration-driven housing crisis is a big one. Canada is an extreme case, but this effect is seen in other countries too. In New Zealand, which has the second highest per-capita migration rates, fertility fell from 2.0 to 1.5 since 2015. In the UK, it fell from 1.77 to 1.43 over the same time period. In these cases too, immigration-led housing shortages seem to be a major part of the story.

What about East Asia?

What about East Asian countries like Korea, China and Japan? They have very little immigration and yet have extremely low birthrates. Don't they undermine this argument?

First, low fertility has multiple drivers. A range of factors have an impact including cultural ones, and it is a mistake to distill birthrates down to just one cause. But second, within-country migration is massive in these countries, contributing to a similar housing dynamic locally.

Even though Korea, China and Japan are all depopulating and have low international immigration, they have extremely high rates of migration from rural areas to a few fashionable cities. The result is similar: young adults are priced out of housing and end up living with their parents, or else they live in tiny apartments. Fertility is exceptionally low in cities like Seoul, Shanghai and Tokyo, compared to the respective countries as a whole.

Everyone can’t live in the same place

When everyone tries to move to the same places, whether within countries or across borders, it is negative for birthrates by creating both crowding and local housing shortages. From a fertility perspective, geographic dispersion is much more pro-natal.

One of the great challenges for solving the global fertility crisis is figuring out how to have economic dynamism that is geographically spread out across many regions and countries. Networked communication can help. The economic benefits of migration will be short-lived if birthrates are so low.