How Excessive Use of C-Sections is Hurting Fertility in Korea and Around the World

In Korea, an incredible 59% of deliveries are by C-section. This is one cause of Korea’s low birthrates since C-sections significantly lower the number of births a woman will have.

These rates in Korea and other countries are far above international guidelines for best maternal and neonatal outcomes (around 10-15 C-sections per 100 births).

Where rates of C-section are high, fertility tends to be much lower, by ~ 1/3 birth/woman in advanced countries.

The same relationship holds for US states. Although the variation in the rate of C-sections is just 23% to 38%, we still see that a higher rate of C-sections is linked to fewer births.

Numerous studies have confirmed this relationship. But why?

Demographer Lyman Stone explains how C-sections reduce future fertility: First, studies find the ability to conceive is reduced after a C-section, likely because of scar tissue in the uterus. Second, doctors advise women to avoid becoming pregnant again after 2-3 C-sections.

But what is going on with Korea? Why are doctors performing so many C-sections in Korea when they are so damaging to a woman's future fertility? Is this medically necessary? Mostly no. The prevalence of C-sections in Korea looks random.

The reason for excessive C-sections is money.

In Korea, doctors are compensated very little for vaginal delivery (one fifth to one third of similar countries). Combined with lawsuit risk, profitability for obstetricians was low. Many OBs went out of business.

Many others increased profitability through C-sections.

C-sections are of course lifesaving for emergencies. But the rate of C-sections shouldn't be above 20%. In Japan, the C-section rate is just 19% and fertility is 50% higher than in Korea.

Meanwhile in Israel, which takes natalism very seriously, just 14% of births are Cesarian.

Birth order shows that C-sections really are a culprit in lower birthrates

How do we know that this is causation and not just correlation? Looking at birth order, Stone found that where C-sections are more prevalent, women stop at just one or two children and are much less likely to have three or more. That is just what you would expect if the mode of childbirth were causing women to choose fewer children in the future.

Excessive C-sections reduce the fertility of mothers in particular

Worse still, over-zealous use of C-sections damages the future fertility of one group in particular, women choosing motherhood.

Getting to motherhood is often a long road and requires many things to come together: finding the right partner, having financial preparation, obtaining housing and then being able to actually get pregnant. Many women don't make it that far.

When those who "make it" have their fertility curtailed because of an unnecessary caesarian, it is a medical failure on the individual level and harmful for society as a whole. After all, in most countries women on average want more children than they are actually able to have.

Fixing financial incentives around delivery is the most cost-effective way to boost birthrates

When we talk about policies that can boost birthrates, most often we think of child tax credits or help with childcare. But fixing incentives for physicians so that they don't favor C-sections delivers a far bigger bang for the buck.

Korea is mulling $70,000 baby bonuses. Meanwhile, the future fertility of the few Korean women willing to become mothers is being diminished because physicians can earn couple thousand more dollars on C-sections.

At a minimum, the compensation for vaginal delivery and C-sections must be brought into parity. Perhaps compensation should be even higher for vaginal delivery, to incentivize doctors to preserve future fertility.

But this is not just a Korean problem. Dr. Neel Shah reported in a Harvard Medical School podcast: “Your biggest risk factor for the surgery is which hospital you go to. C-sections in this country vary between 7% and 70% by hospital. It’s tenfold risk, depending on where you go.”

The root of such differences is almost always skewed incentive structures, which need to be fixed.

Multiple C-sections are usually fine!

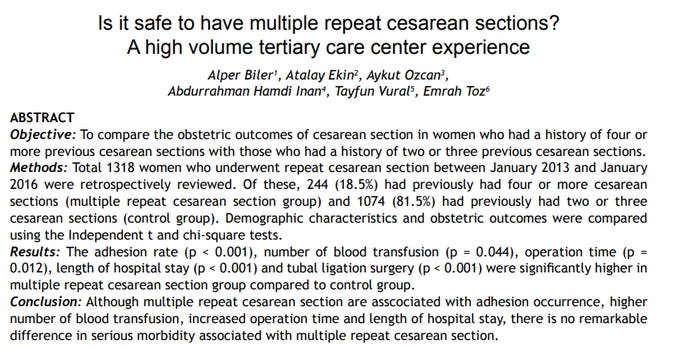

A study in Turkey looked at what happens when women have a lot of C-sections. Is it as bad feared?

Probably not! Among 244 women who had four or more C-sections, there was indeed a higher rate of complications compared to 1074 women who had 2 or 3. But there wasn't a single maternal death in either group!

It may be that doctors are being too conservative in advising women with multiple caesarians to avoid pregnancy. Women who want more children should probably go for it, regardless of their history!