The Long Shadow of China's One Child Policy

China's one-child policy is over. Yet the fertility in China keeps falling, and was just 1.02 births per woman in 2023.

China's one-child policy was finally ended in 2015. One impetus for its ending was the uproar over the forced abortion of Feng Jianmei in 2012, after graphic pictures went viral in China.

Whatever arguments had existed for China's one-child policy, those arguments made no sense in 2012. China's ability to feed itself was not doubt, and its fertility had been below replacement for two decades.

Yet local officials kept up the policy with grotesque fervor.

The stories of China's one child policy enforcement are excruciating, made sadder by the realization that it was all so unnecessary, and that China would soon be facing a crisis of rapid demographic decline.

One way the policy was enforced was to deny citizenship papers to children born in violation of the policy, crippling their future. He Shenguo killed two officials for refusing to register the birth of his child. Here, He says goodbye to his wife before his execution.

To this day, millions born in violation of the policy remain as second-class citizens, without any papers in the only country they have ever known.

Paul R. Ehrlich's panic-inducing 1968 book The Population Bomb had a profound impact on CCP leadership, and was a big reason for the one-child policy. Ehrlich's anti-natal ideology has many destructive offshoots today, including the human extinction movement.

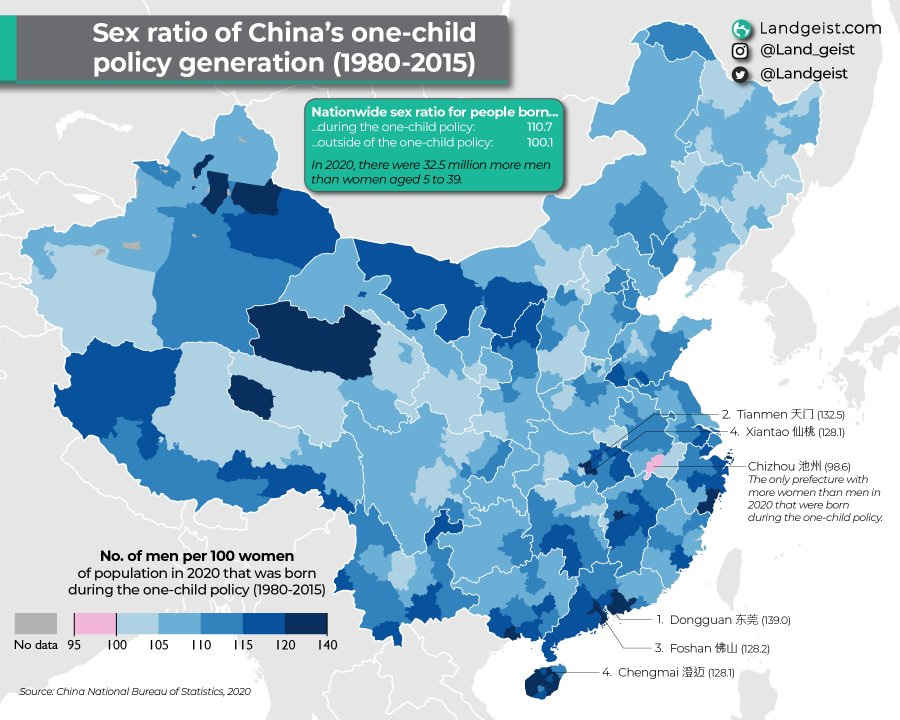

One of the lingering effects of China's policy is a population imbalance between men and women, with up to a 40% 'excess' of young men in parts of China.

Although China desperately wants to raise birthrates now, there weren't enough young girls born to be wives and mothers today.

But even worse, the Confucian pro-family culture that had sustained China for millennia was virtually wiped out. In some northern provinces where the policy was more strongly enforced, fertility remains only half that of the south, where the policy was less strongly enforced.

China's fertility is likely to drop even more from here because fertility intentions among Chinese young people are the lowest in the world.

What can China do to get its birthrate up?

China might start by not persecuting the few higher fertility groups that remain. Even as China claims to want to raise its birthrates, it continues to push mass sterilization and forced abortion on the Uyghur minority in Xinjiang. China will have to fully close the book on its population control era, and sincerely acknowledge past mistakes, or else pro-natal efforts will be met with cynicism.

Across the board, China may have to embrace religious freedom if it wants higher fertility subcultures to take root.

Demographer William Huang writes:

"The CCP would never tolerate any closed-off religious community to exist. Let’s face it: the Amish only exist because the US Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, and the principle is actually enforced in America. Horse and buggy-riding Amish would be sent off to labor camps, their children forcefully re-educated, or the women simply sterilized en masse if such a community ever attempted to establish a footing in China."

Let's hope Huang is wrong. Maybe China will permit freedom of belief when it recognizes that such varied cultures could play a key role in a demographic recovery, just as they are a major part of America's vitality.

Apart from religion, China's work culture is a problem. China's so-called 996 culture (working 9 am to 9 pm six days a week) hardly leaves time for a social life, let alone a family.

Finally, China's building style in recent decades has surely been anti-natal, a sea of high-rises in every city. Perhaps China is stuck with the housing stock it has built, unless it is prepared to tear down modern high-rises.

But going forward, China ought to build as many single-family homes as possible, to at least give those who want to try to have a bigger family something to work with.