What should a newly elected leader in a low-birthrate country do to boost fertility rates?

Eight avenues for leaders and policymakers to revive birthrates.

The year 2024 is the biggest year for elections we’ve ever had. More than 2 billion voters will participate in elections in more than 50 countries. Most countries having elections face birthrates that are too low, and many of the new leaders will be thinking about the birthrate crisis, hoping to improve their nations’ outlooks by boosting family formation.

What can new leaders do to boost birthrates that will be both feasible and effective?

1. Talk about the issue a lot. With data.

The first thing leaders concerned about the fertility crisis need to do is talk about the problem. Family formation is not something a government can just do on its own, like building a bridge or giving a tax cut. There must be buy-in and belief in the importance of having children across society. And so, communicating about the problem is critical.

If you spend a lot of time on certain parts of Twitter/X, you know that low birthrates are a serious problem. But surveys show that wider awareness of the birthrate crisis is still very low.

Even as many economists and assorted policy thinkers grow alarmed, most folks aren’t even thinking about birthrates yet. Even more, a large share of the public still has the 1960s mindset of overpopulation fear, and thinks society must take action to curb fertility. This while actual fertility numbers have moved toward decline or even collapse – across the developed world.

How can one talk about the issue without seeming like an ideologue and turning people off?

Just stick to the data. Fertility rate and replacement fertility are simple and useful concepts and once people learn that fertility is far below replacement in most countries, they do not forget it. The actual data quickly breaks through the lie that overpopulation is the crisis we face.

Communication is essential. Compare France and Canada. Both aim to have generous social support for families. But in France leaders from various parties talk openly about the need for more children, while in Canada leaders do not. France’s fertility was 1.68 in 2023 vs. 1.25 for Canada.

2. Focus on bipartisanship

A big risk is that pronatalism becomes so politicized that one side becomes more anti-natal in response to the other side becoming more pronatal.

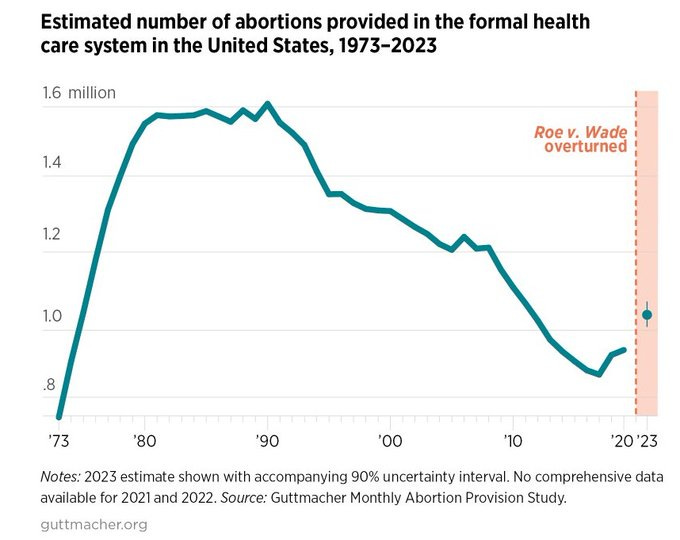

Conservatives cannot move national culture effectively without working in concert with liberals. Consider what has happened recently with abortion in America. Through the Dobbs ruling, conservatives against abortion were able to enact bans in a partisan way in various US states. Yet in the end there are more, not fewer, abortions in America than before!

When conservatives acted without buy-in from the left, the resulting backlash was so strong that culture moved in the opposite direction.

Committees, policymakers and communicators addressing the fertility crisis need to be drawn from across the political spectrum where possible, with intense focus on bringing in left-off center people. The risk and general tendency is for pronatalism to have too much representation from the right and too little from the left. If that inspires a backlash, then the whole effort could be for naught. Korea and Poland both have both failed to boost birthrates for this very reason as conservative governments failed to get the buy-in of young liberal women.

3. Enlist cultural leaders in messaging

In Korea, stodgy old conservative politicians are desperate to spur a baby boom while the real people with social power and influence sing in K-POP bands. The members of BTS are all around 30 and childless, and most are single.

For fertility, culture matters more than policy, and the culture of young people matters most of all. While policy nerds may be persuaded by platforms of political parties, most regular folks are far more in tune with musicians, athletes and other influencers than they are with politicians.

4. Make space for religious faith groups to thrive

One of the biggest cultural factors that is associated with higher fertility is religiosity – both because faith instills beliefs around having children and because faith communities provide family friendly social networks. Studies show that regular religious attenders have significantly more children than those who never attend.

Of course, government in a free country cannot and should not make people adopt faith. In the United States, it would go against the Establishment Clause of the Constitution for the government to push religious belief.

Still, there is a lot that governments can do to create a culture where faith groups can thrive:

Provide broad tax exemptions for faith groups

Ensure religious freedom, including for smaller faith groups.

Allow school choice, whereby families can choose to allocate their education funds to faith-based schools if they so choose.

America is more religious and fertile than Europe even though many European countries have established churches while America takes a hands-off approach. The reason? Religious freedom and pluralism mean that churches in America work to meet the needs of their adherents, lest they seek faith and community elsewhere.

This dynamic of pluralism has seen nondenominational churches with entrepreneurial leaders grow in America, filling a void as most mainline churches have gone into decline.

5. Encourage and support building of housing, but with a strong bias favoring lower density and suburbs and disfavoring urban apartment blocks

A lack of housing and high housing costs are a big impediment to family formation and the data confirms this. Young people who cannot leave their parents’ homes tend to have much lower odds of having children than those who are able to establish their own households.

But for family formation it matters greatly what is built. East Asia has seen a flurry of building over the past 30 years, dramatically increasing square footage, and yet fertility rates there are now the lowest in the world. There are multiple causes of this.

Yet it is a remarkable fact that the fertility rate in Seoul, Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong are all in the vicinity of 0.5-0.6 births per woman while each of these cities is a veritable sea of high-rise apartment towers. Tokyo doesn’t fare much better, having the lowest fertility in all of Japan despite having millions of surprisingly inexpensive apartments.

Lessons on how to build in a way that is pronatal can be drawn from America’s own 1946-1964 Baby Boom. That era saw a surge in homebuilding, and specifically of single-family homes on lots in new subdivisions spreading out from cities. Buoyed by cheap home loans backed by the government, Americans had more children than they had in 50 years.

As demographer Lyman Stone explains in his new paper More Crowding, Fewer Babies: The Effects of Housing Density on Fertility (June 2024) perhaps the most pronatal type of building is “dense-single-family with mixed-use zoning built on greenfield sites in exurban areas.” Some things governments can do with housing to encourage family formation:

Open many greenfield sites for new suburban subdivisions. In the US this should especially include Western federal lands.

Recognize that height restrictions may actually be a good thing for birthrates: If zoning rules are stopping huge towers being built, that could be positive for family formation because such anti-natal housing drags down fertility for generations once built.

Provide strong financing and mortgage options specifically geared to young people to help overcome a big generational divide on housing.

Limit immigration to sustainable levels. Canada has seen a collapse in birthrates in part because extremely high levels of immigration have overwhelmed housing supply and caused affordability to plummet.

6. Health classes for young people geared toward awareness of unplanned childlessness, the fertility window, and the benefits of marriage

One of the paradoxes of the modern life is that actual fertility is far below desired fertility in the United States and in most of the world. If people could only have the children they desire to have, there would not be a low birthrate crisis!

As Stephen Shaw, creator of the BirthGap series has documented, a major cause of low birthrates is unplanned childlessness. Often this reflects people running out of time before being able to have children. Shaw discovered that when young people learned how common it is for people to fail to have the children that they hoped for, their whole outlook and plans changed.

Sex-Ed in high schools is geared toward avoiding unplanned pregnancy and ignores the opposite problem which is more widespread today: unplanned childlessness.

One can boost fertility through health education for high schoolers that focuses on three simple things:

Awareness of the low birthrate problem and the pervasiveness of unplanned childlessness

Knowledge of human fertility including the fact that fertility is highest in the 20s and falls sharply throughout the 30s

The value of marriage as a vehicle for achieving family goals, especially marriage that comes early enough in life

7. Support of childcare, especially through deregulation

Childcare costs are an enormous weight on many middle-class families. Subsidies are likely to help fertility rates somewhat. But high costs reflect a shortage of childcare supply. Many parents face years-long waitlists.

Lawmakers in the US have also balked at subsidies, given the costs. Yet there is a way to both increase childcare supply and reduce costs. That way is to deregulate childcare. That means removing limits on the number of children and allowing more staff per child, as well as removing degree requirements for staff. That can reduce cost per child and increase childcare availability, by making childcare a more profitable business.

A newly published paper, Childcare Regulation and the Fertility Gap (Flowers et al., May 2024) shows that quality and safety of childcare does not go down when it is deregulated, while fertility rates are boosted. Truly the nearest thing to a free lunch!

8. Tax policy that favors large families

France has taken leadership in pronatal policy in Europe and has been rewarded with Europe's highest fertility rates, among French natives and immigrants alike.

The cornerstone of the French system is the ‘quotient system’ of taxation. Price Waterhouse Coopers describes it like this: “Under income-splitting rules, total taxable income is divided by the number of shares awarded to the taxpayer: one share for a single person, two shares for a married taxpayer without children, half a share for each of the first two dependent children, and one full share for the third and each subsequent child.”

A good way of thinking about this for Americans is by noticing how a married couple with X income is in a much lower tax bracket than a single person with X income. Their combined income has much higher thresholds for each tax bracket than a single person would have. (That American tax policy is itself somewhat pronatal, by encouraging marriage for many.) Now imagine that math for children as well. In France, each additional child has a similar effect as a spouse for tax purposes, by moving the total family income into lower tax brackets. This is a great system for favoring larger families, which are crucial for turning around low birthrates.

But after France cut this benefit for higher-income families a study found their births fell 40%. This shows that pronatal tax policies should not be income dependent but apply across the income spectrum. The goal of such policy should not be welfare, but to reflect the need for and value of children across society.

Communication is essential

This essay proposes eight avenues for leaders and policymakers to revive birthrates. Four pathways center around communication: Building awareness of the issue, seeking bipartisanship, enlisting cultural leaders, and using health curricula that informs young people about the high odds of unplanned childlessness. This reflects the high importance of culture in family formation.

Tax policy and childcare are more traditional pathways for pronatal policy, and they make a real difference. Housing policy too matters a great deal, but too often leaders are agnostic about the type of housing. Housing type matters greatly: Single family housing boosts fertility while dense apartment towers lower it; it is essential for policymakers to heed the warning of Asia and favor the former while resisting the latter.

Finally, with religiosity as one of the main drivers of birthrates, it is essential for leaders to create a climate where many faith groups can thrive, while respecting the choices of everyone.

I've written a list of ideas that could boost Western fertility rates here: https://zerocontradictions.net/faqs/overpopulation#boosting-western-fertility